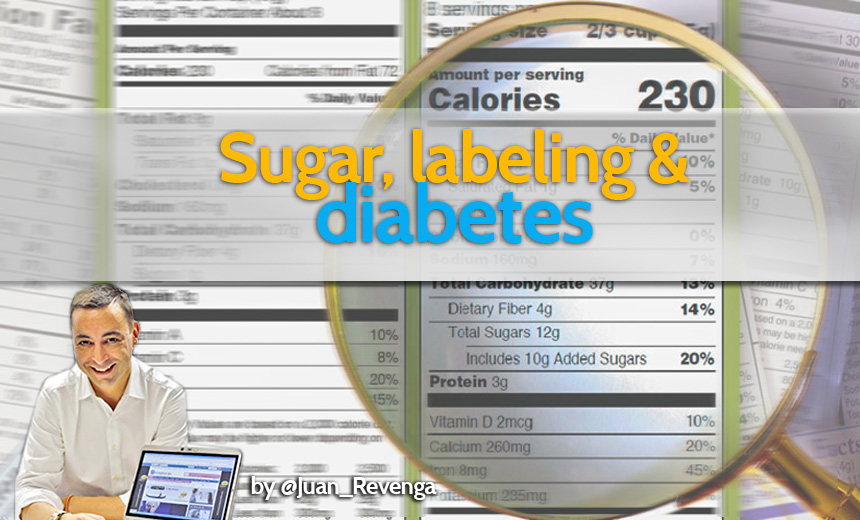

Sugar, labeling and diabetes

Far too easily, and quickly too, we relate concepts such as rain and umbrella, hammer and clove, soup and spoon … and we do the same with diabetes and sugar.

When we hear ‘diabetes’ we immediately think of ‘sugar’; so much so that many people believe that sugar is the only issue affecting people with diabetes: ‘the problem’ just sugar, and not much more.

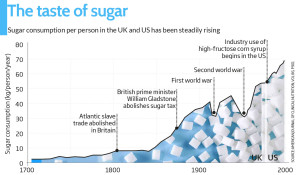

But sugar is everybody’s issue. I mean, nowadays the whole population is living with sugar up to their necks. This is highlighted by the World Health Organization in its ‘Guide to Sugar Intake for Children and Adults’ when you can’t get enough warning signs about this ingredient. Eloquent as few is this curve that represents the consumption of sugar in the last three centuries: we have gone from having an average consumption per inhabitant and year of approximately 3-6 kg in the eighteenth century to about 70 kg today.

But sugar is everybody’s issue. I mean, nowadays the whole population is living with sugar up to their necks. This is highlighted by the World Health Organization in its ‘Guide to Sugar Intake for Children and Adults’ when you can’t get enough warning signs about this ingredient. Eloquent as few is this curve that represents the consumption of sugar in the last three centuries: we have gone from having an average consumption per inhabitant and year of approximately 3-6 kg in the eighteenth century to about 70 kg today.

The real problem with people with diabetes is that, based on several factors – genetic and lifestyle – they end up with insulin resistance, so that insulin does not perform its function properly, and therefore blood glucose levels rise above what would be healthy. But let’s not fool ourselves, the problem with access to the enormous amount of sugar that surrounds us (in any of its forms) is everyone’s problem.

It is time to identify the amount of sugar present in food and to know the tools to properly interpret the labeling.

STEP ONE: fresh farmer-market food is fine

Keep in mind that we only must worry about the sugar present in ultra-processed foods or that sugar that the

Free sugars are all those sugars added by the user or incorporated by the manufacturer in the preparation of any processed product. By way of exception, the WHO also considers ‘free’ sugars those that are present in a food thanks to its special availability, even if there is no “addition”, for example those of honey and those present in juices.

On the other hand, the sugars present in milk, whole and fresh fruits and vegetables are considered ‘intrinsic’. Thus, in the words of the WHO itself, they should not be negatively considered when choosing these foods.

STEP TWO: understanding sugar claims in labeling

Suppose you are no longer in the farmers market and you find yourself in front of a product that has its packaging and labelling and that there is something in it that refers to its sugar content. It could be such as:

- Low sugar content: European Regulation 1924/2006 states that a food could be labeled as low in sugar if the product does not contain more than 5g of sugar per 100g for solid foods or 2.5g of sugar per 100 ml for liquids.

- Sugar-free: the same text states that a food does not contain sugar if the product does not contain more than 0,5 g of sugar per 100 g or 100 ml.

- No added sugars: A claim that no sugars have been added to a food may only be made where no monosaccharide or disaccharide, or food used for its sweetening properties, has been added to the product. If sugars are naturally present in foods, the following indication shall also appear on the labelling: “contains naturally present sugars“.

However, we must call for precaution. I will explain. Such statements about sugar (or any other ingredient) can be compared to when a terrorist says he doesn’t carry a gun; and it may be true, but he can hide a knife or a machine gun or another weapon. In other words, having little or no sugar does not imply, at all, that the nutritional profile of that product is healthy. Either because of its lipid profile, its amount of salt, its high energy intake … or whatever. Remember that in the end this type of statements is only possible in the products of the supermarket, not those at the farmers market.

STEP THREE: Discover hidden sugar and all its pseudonyms

Another important tool to discover the sugar that we incorporate is to read the list of ingredients and discover the sugar that includes a product without the word “sugar” in it. Thus, it is not uncommon that in order to avoid mentioning “sugar” the manufacturer incorporates other ingredients without mentioning it. The most common are cane juice, honey (of any origin), high fructose corn syrup, dextrose, fructose, sucrose, fruit concentrate, glucose, invert sugar, maltose, or syrup (whatever). All of them can also be given different adjectives that usually turns to a healthy pleasing image to consumers, for example: organic or natural maple syrup … when and facing what really matters is pure sugar. Remember that, in the end, the sugar in your sugar bowl could be called organic beet sucrose (if that beet was certified as organic).

.

FINAL STEP: run away from “diabetic” labeled foods.

The pretext to label a product as special “for diabetics” often based on the reduction of energy intake, fat, also the replacement of sugars non- caloric or other sweeteners, or the exchange of certain sugars, typically fructose. However, we must be aware that this type of food is not justified unless they are considered within the framework of a balanced, varied and healthy diet. In fact, one of the most prestigious guidelines in the management of type 2 diabetes, that of the British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) states without doubt that “the use of foods marketed specifically for diabetics is discouraged” (point 1.3.8).

Latest posts by Juan Revenga Frauca (see all)

- Obesity recognized as a chronic disease - 13 October, 2021

- Who said you have to eat everything? - 7 October, 2021

- Diabetes and Alzheimer - 29 January, 2021